Practising community-led development

Practising community-led development

Steve Fisher

On the face of it, community-led development ought to be straight forward. A group of people with common interests decide on a goal they wish to achieve or a problem they want to tackle. They enlist external support, usually meaning technical knowledge, materials and funds. Then they develop a plan for something that is probably called a project. They go ahead and implement it.

In the process of developing a new course on practising community-led development, I have been thinking about what makes the subject more complicated in practice than it might seem from the outside. A starting point is to set out the parameters. Examples of community-led projects fall into four categories:

- Local infrastructure improvements, such as roads, water supplies or better housing

- New or improved enterprises or services to address gaps in, for example, childcare or education

- Initiatives designed to tackle problems that the community might be experiencing, such as conflict or homelessness

- Projects to build local skills and capacity for specific purposes, such as youth leadership or community governance.

The basis for successful projects are the methods and techniques, skills and aptitudes that define community-led development practice. Applied with skill and care, they enable the objectives of a project to be achieved. But communities are complex, so nothing is easy.

At the centre of most projects are a set of relationships between the community, an implementing organisation, some specialised contractors and a government agency or a private funder (or both). The decision-making processes, the power and the authority that are exercised through those relationships have a profound influence on the eventual outcomes. This means that the agreements between parties and the way they are applied are fundamental.

The question of which people from the community participate in the project and how they participate has long exercised anyone who has worked in this field. Strategies that consider the priorities of different population groups within the community, as well as those from outside the project who may be affected by it, are central to effective practice. The roles of women, men, young people, people with disabilities and minority groups within the community need to be defined, especially when key decisions are being made.

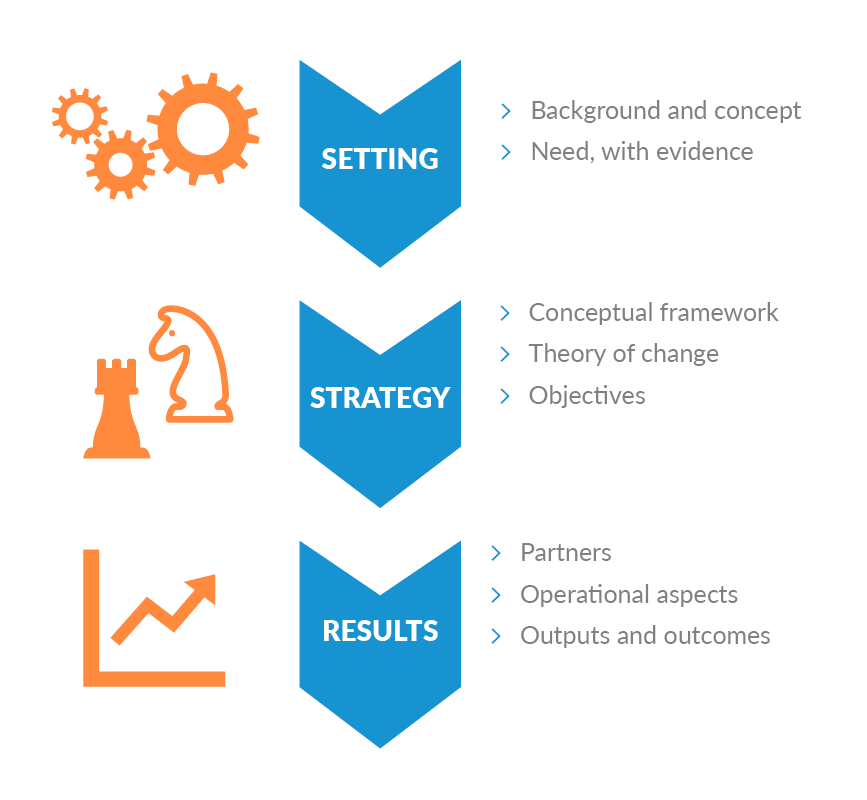

All projects need to be designed. In other words, they require the parts to be brought together in a way that enables them to be implemented. These components include clear objectives, a team, resources and knowledge and a set of defined and scheduled activities (the actual work to be done).

Similarly, all projects must be managed in an accountable way to enable the design to be implemented. The role of data is central to effective project management, whether to gauge progress, to obtain the right measure of needs and priorities of the community or in the monitoring and evaluation of the work. Processes for learning and improving through the data collected are also part of the overall picture.

Given that community-led projects are concerned with improving the health, welfare, safety, prosperity and happiness of people, then considerations of ethics and equity are central to practising community-led development.

As we develop the course, I will provide further updates through the Community Works blog.