Developing, implementing and evaluating health promotion resources for high school students in the Northern Territory

Developing, implementing and evaluating health promotion resources for high school students in the Northern Territory

The Cancer Council Northern Territory invited Community Works to support a program they developed, the School Smoking Education Program (SSEP). The purpose of the program was to educate students through evidence-based information about the harmful impacts of cigarette smoke and e-cigarette vapours. The target audience was 12-16 year olds, focussed on students in years 7, 8, 9 and 10 attending schools in Darwin and Palmerston.

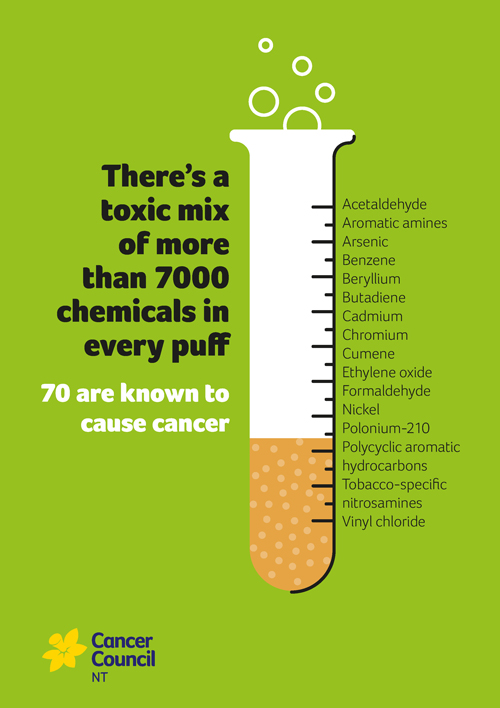

The program was implemented into the school curriculum and it ran over four lessons covering topics that included the health implications of tobacco, chemicals and nicotine addiction, social determinants of health, societal factors in tobacco use and smoking cessation methods. The intended outcome of the program was to reduce the number of adolescents who take up smoking and increase the number who quit smoking if they are already smokers.

Cancer Council NT staff designed the program and delivered the sessions in each school. Community Works supported them through the design of resources for the program and by assisting with the evaluation of student responses to the program in each school. The design and framing of resources by Community Works carefully considered literature on the key concerns and most important issues impacting adolescents aged 12-16. For example, this included an emphasis on concerns about the environment and about family members becoming seriously ill. The resources also took into consideration the increasing trend of adolescents to take up e-cigarettes or vaping.

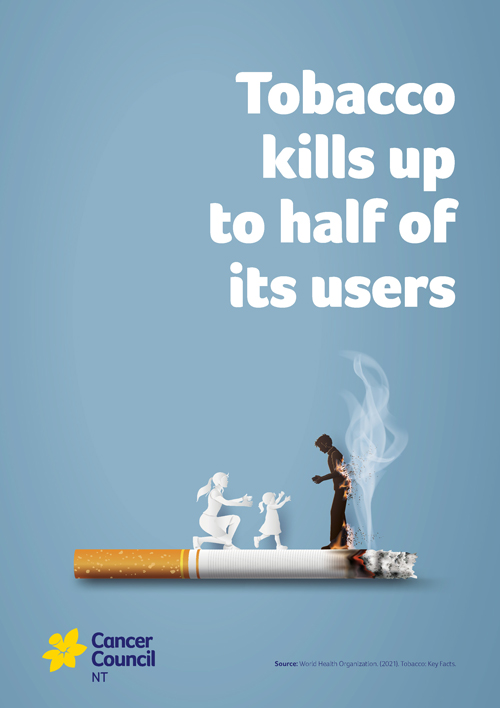

Examples of the resources are shown below. They were designed for use across multiple formats including as posters, magnets and pamphlets, as well as on social media.

In addition, the flyer provided to all students included explanations of the wider social and environmental effects of tobacco production and use.

Cancer Council NT considered an evaluation of the program to be very important as a means of gauging how well the materials had been understood by students and what the likely impacts would be on their knowledge, attitudes and behaviours relating to smoking. An evaluation would also help to show any changes or improvements that could be made to the program in the future.

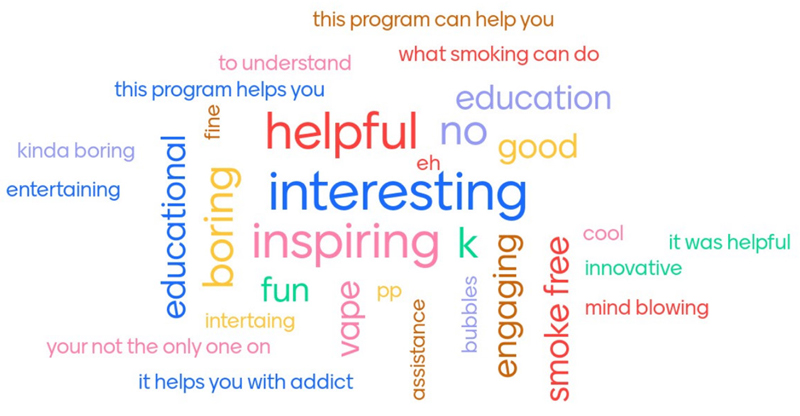

As an engaging and efficient strategy for the evaluation, we recommended choosing a small number of questions and then putting them to students through Mentimeter, an online platform that enables a range of question-types to be developed, such as open-ended, survey or multiple-choice questions. Mentimeter enables responses from a group of people to be immediately presented and analysed according to different formats that could be chosen in advance by Cancer Council NT staff. For example, one question asked students to write down three words that represented their reactions to the program. The format we chose to present the results was a word cloud like the one below, with most common reactions shown in larger font.

This approach was engaging to students because they could respond anonymously to questions using mobile phones or tablets and the combined responses could then be projected on a screen and discussed with the group as a whole. Given the limitations of time available within a school timetable, each evaluation was scheduled to only require twenty minutes at the end of the final session. After evaluations were completed in all four schools, Community Works produced a short report that summarised the findings.

We anticipate that our relationship with Cancer Council NT will continue into a further phase of work as the organisation scales up its work to reach more schools and students in the future.